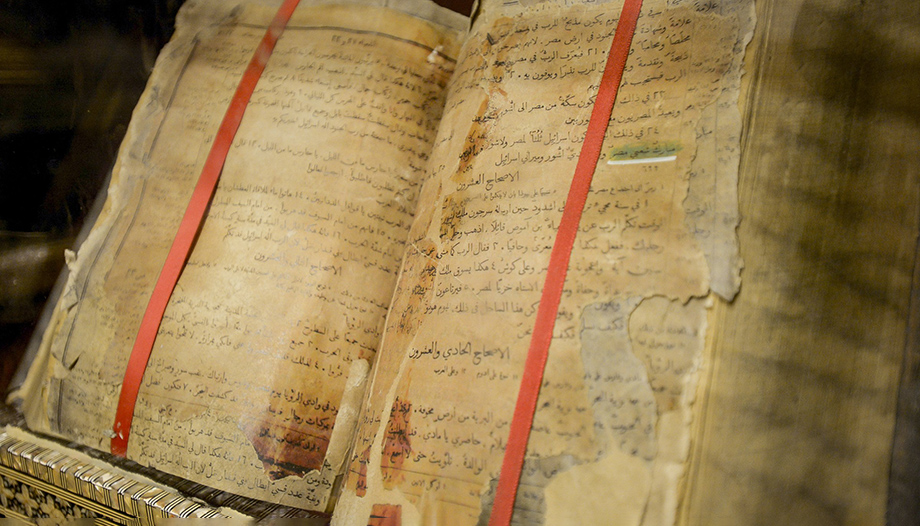

Christianity, although it was born with a book in its cradle - the image comes from Luther for whom the Bible was the manger where Jesus was laid -, it is not a book religion but a religion of tradition and scripture. So was Judaism, especially before the destruction of the Temple. This note is clear when speaking of comparative religions. (M. Finkelberg & G. Stroumsa, Homer, the Bible and beyond: literary and religious canons in the ancient world)..

However, a succession of factors - more practical than theoretical - have led to some confusion. Collective memory theorists (J. Assmann) point out that 120 years after a founding event, the communicative memory of a community is embodied in a cultural memory, where cultural artifacts create cohesion between the past and the present.

However, religious or cultural communities that survive over time are characterized by prioritizing textual connectivity over ritual connectivity.

This is more or less what happened at the beginning of the third century in the Church, when theology was conceived as a commentary on Scripture. Later, with the appearance of Islam, a religion of the book from its origin, and the development of Judaism as a religion without a Temple, the idea of religions of revelation was assimilated with religions of the book: Christianity, a religion of revelation, was thus placed in a place that was not its own: a religion of the book.

In a third moment, Luther and the fathers of the Reformation, with the reduction of the idea of tradition to mere Church custom (consuetudines ecclesiae)rejected the principle of Tradition in favor of the Sola Scriptura.

Finally, the Enlightenment with its distrust of tradition only accepted an interpretation of Scripture that was critical, also and above all, of tradition.

In the communities of the Reformation, the succession of these factors led more often than not to a double direction in the interpretation of Scripture: either the message was dissolved in the secularism proposed by the critics, or the critics were dispensed with and ended up in fundamentalism.

Tradition in the Catholic Church

In the Catholic Church, on the other hand, the approach was different. Since Trent, it referred to the apostolic traditions -those of apostolic times, not the customs of the Church- as inspired (dictatae) by the Holy Spirit, and then transmitted to the Church. Therefore, the Church received and venerated with equal affection and reverence (pari pietatis affectu ac reverentia) both the sacred books and those other traditions.

Later, the Second Vatican Council clarified somewhat the relationship between Scripture and Tradition. It first affirmed that the apostles transmitted the word of God through Scripture and traditions - Tradition is thus conceived as constitutive, not merely interpretative, as is the case in the Protestant confessions - but it also pointed out that, by inspiration, Scripture transmitted the word of God being word (locutio) of God.

Tradition, on the other hand, is merely a transmitter of the word of God (cfr. Dei Verbum 9). He also proposed it from another perspective: "The Church has always venerated the Sacred Scriptures as the Body of the Lord Himself. She has always considered and still considers them, together with Sacred Tradition (a cum Sacra Traditione), as the supreme rule of their faith, since, inspired by God and written once and for all, they unchangeably communicate the word of God himself." (Dei Verbum 21).

We must not lose sight of the fact that the subject of the sentences is Sacred Scripture. But in the Church, Scripture has always been accompanied and protected by Tradition. This aspect has been taken up, at least in part, by Protestant thinkers who, in the ecumenical dialogue, make use of the expression Sola Scriptura numquam solaThe principle of the Sola Scriptura in Protestant logic refers to the value of the Scripture, not to its historical reality, which is certainly nunquam sola. It can therefore be affirmed that the Catholic and Protestant positions have come closer together. However, the core of the question remains the intrinsic relationship between Scripture and the traditions within the apostolic Tradition, that is, that which was handed down by the apostles to their successors and is still alive in the Church.

Apostolic tradition

It has been noted many times that Jesus Christ did not send the apostles to write, but to preach.

Certainly, the apostles, like Jesus Christ before them, made use of the Old Testament, that is, the Scriptures of Israel. They understood these texts as an expression of God's promises - and, in this sense, also as prophecy or proclamation - that had been fulfilled in Jesus Christ. They also expressed the instruction (torah) of God to his people, as well as the covenant (disposition, testament) that Jesus brings to fulfillment.

The texts of the New Testament, for their part, were not a continuation or an imitation of the texts of Israel. None of them is presented, either, as a compendium of the New Covenant. They were all born as partial - and, in some cases, circumstantial - expressions of the Gospel preached by the apostles.

In any case, in the generation that followed that of the apostles - as in St. Paul before, when he distinguished between the Lord's command and his own (1 Cor 7:10-12) - the principle of authority was in the words of the Lord; then, the words of the apostles and the words of Scripture. This is seen in the apostolic fathers, Clement, Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, etc., who mention indistinctly, as an argument of authority, the words of Jesus, the apostles or the Scriptures.

However, the textual form of these words almost never coincides with that which we have preserved in the canonical texts: the texts functioned more as a memory aid for oral proclamation than as sacred texts.

A change of attitude is observed in the last decades of the second century. Two factors contribute to this change.

On the one hand, Christianity comes into contact, and is contrasted, with developed intellectual worldviews; specifically, with Middle Platonism - a Platonism bathed in moral stoicism - and with the gnosis of the second century, which proposed salvation through knowledge. Some Gnostic teachers saw in Christianity - the expression was born with Ignatius of Antioch - a religion that could be in accordance with their conception of the world. Basilides, at the beginning of the second century, was perhaps the first who understood the writings of the New Testament as foundational texts for his Gnostic teaching, and others such as Valentinus and Ptolemy, already in the second half of the second century, were acute interpreters of the Scriptures, which they made coincide with their system.

St. Justin, a contemporary, and perhaps colleague, of Valentinus, already pointed out that the teachings of these teachers dissolved Christianity into Gnosticism and that, therefore, their authors were heretics - it is Justin who coined the word with the sense of deviation, since before it only meant school or faction -, although without proposing profound reasons. On the other hand, at the end of the second century, the idea of a reliable oral tradition had already weakened: there are no longer - perhaps St. Irenaeus is the exception - disciples of the disciples of the apostles. When this happens in a cultural or religious community, as has been noted, the communities establish artifacts that preserve a certain cultural or religious memory, and the artifact of connectivity par excellence is writing.

The great Church, looking askance at the Gnostic heretics, made three decisions that together preserved her identity. Benedict XVI (cf. Speech at the ecumenical meeting, 19-08-2005) referred to them more than once: first, to establish the canon, where Old and New Testaments form one Scripture; second, to formulate the idea of apostolic succession, which takes the place of the witness; finally, to propose "the rule of faith" as a criterion for interpreting Scripture.

The importance of St. Irenaeus

Although this formulation can be found in many theologians of the time - Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Hippolytus, Tertullian - on the eve of the 1900th anniversary of his birth, it is almost obligatory to look to St. Irenaeus to discover the modernity of his thought.

His most important work, Debunking and refutation of the pretended but false gnosispopularly known as Against heresies, The first part of the book follows all that has been said up to now. After a few prefaces, it begins as follows: "The Church, spread throughout the orb of the universe to the ends of the earth, received from the Apostles and their disciples faith in one God the universal Sovereign Father, who made... and in one Jesus Christ the Son of God, incarnate for our salvation, and in the Holy Spirit, who through the Prophets....". St. Irenaeus follows the text with a formula that in other places he calls the "rule [canon, in Greek] of faith [or of the truth]". This rule of faith does not have a fixed form, since, handed down by the apostles, it is always transmitted orally at Baptism or in baptismal catecheses. It always refers to the confession of the three divine persons and the work of each of them.

It is recognizable throughout the Church, which "carefully guarding it, [...] and preaches, teaches and transmits it [...]. The churches of Germania do not believe differently nor do they transmit any doctrine different from that preached by those of Iberia." (ibid. 1, 10, 2). Therefore, like apostolic Tradition, it is public: "is present in every Church to be perceived by those who really want to see it". (ibid. 3, 2, 3), unlike the Gnostic, which is secret and reserved to the initiated.

In fact, the rule could be sufficient, since "many barbarian peoples give their assent to this ordination, and believe in Christ, without paper or ink [...], with care they keep the old Tradition, believing in one God [follows another Trinitarian confession, an expression of the rule of faith]" (ibid. 3, 4, 1-2).

Nevertheless, the Church has a collection of Scriptures: "True gnosis is the doctrine of the Apostles, the ancient structure of the Church throughout the world, and what is typical of the Body of Christ, formed by the succession of bishops, to whom [the Apostles] entrusted to the churches of each place. Thus comes to us without fiction the custody of the Scriptures in their entirety, without taking away or adding anything, their reading without fraud, the legitimate and affectionate exposition according to the Scriptures themselves, without danger and without blasphemy." (ibid. 4, 33, 8).

It is on the last point that attention should be focused. The rule (canon) of faith is he who interprets the Scriptures correctly (ibid. 1, 9, 4), because it coincides with them since the Scriptures themselves explain the rule of faith (ibid. 2, 27, 2) and the rule of faith can be unfolded with the Scriptures, as St. Irenaeus does in his treatise Demonstration (Epideixis) of apostolic preaching..

This interpenetration between the rule of faith and the Scriptures explains other aspects well. First, each of the Scriptures is correctly interpreted through the other Scriptures. Second, over time, the word "rule/canon", is applied first of all to the canon of the Scriptures, which is also the rule of faith.

Professor of New Testament and Biblical Hermeneutics, University of Navarra.